by Dr. Scott Pegg

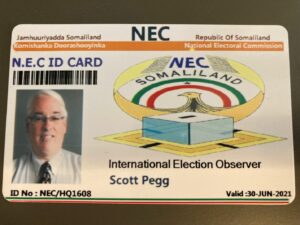

In 2017, I travelled to the unrecognized Republic of Somaliland as an international election observer for their presidential elections. In May 2021, I again had the chance to return to Somaliland as an international election observer for their parliamentary and local council elections held on May 31, 2021. This time, I was part of the “Limited International Election Observation Mission” organized by Professor Michael Walls at University College London. The mission was funded by the British foreign office but was independent from it and international in nature. We were invited to Somaliland as guests of the National Electoral Commission (NEC). In contrast to 2017, when we had 30 teams of two observers each, in 2021 due to COVID-19 and other factors, we only had six teams of two observers each. Observers came from a variety of different countries including Egypt, Ethiopia, France, Germany, New Zealand, South Africa, the United Kingdom and Zambia. I was the only observer from the United States on this mission.

Although it remains entirely unrecognized by the international community, Somaliland is not new to electoral democracy. Somaliland had a constitutional referendum in 2001 that was widely perceived as a referendum on its independence from Somalia. It has also held three previous direct presidential elections (2003, 2010, 2017), two previous local council elections (2002, 2012) and one previous parliamentary election (2005). As Michael Walls and I have written elsewhere, Somaliland’s democracy “juxtaposes striking successes with recurrent and persistent problems.”

The 2021 parliamentary and local council elections were significant for several reasons. First, Somaliland’s members of parliament had served 11 years beyond the ostensible five-year mandate they secured in 2005. The country has a presidentially dominated system of government, but the parliament’s lack of a reasonably current democratic mandate weakened it and greatly hurt its perceived legitimacy. Second, this was the first time Somaliland had conducted two elections (parliament and local council) at the same time. This introduced additional complexities into everything from campaigning and voter education to physically delivering and counting the ballots. Finally, these were the largest elections ever held in Somaliland with 1.065 million registered voters, 2,709 polling stations, 30,000+ poll workers, and 552 candidates contesting 220 local council seats and 246 candidates contesting 82 parliamentary seats. Alas, out of 798 total candidates, only 28 (3.5%) were women (down from 5.91% women candidates in the 2012 local council elections), even though women almost certainly accounted for more than 50% of the total votes cast in the elections. None of the 13 women candidates running for parliament won a seat, lending credence to the long-standing critique that Somaliland is “a male democracy.”

For the 2021 elections, my team and one other team were posted to Burao, Somaliland’s second largest city. In 2017, I was also posted to Burao but assigned to the rural areas south of it. This time, we stayed within the city to maximize the number of polling stations we could observe. Spending about 30 minutes at each polling station, my team was able to observe 15 different polling stations in the western half of Burao.

Article Nine of Somaliland’s Constitution mandates the existence of not more than three political parties in Somaliland. This election was contested by candidates from the Kulmiye (Peace, Unity and Development Party), UCID (Justice and Development Party) and Waddani (Somaliland National Party) Parties. The entire country was plastered with campaign ads. To assist illiterate voters, each local council candidate also had a number (101, 203, 305, etc.) and each parliamentary candidate had a symbol (camel, tortoise, lightbulb, etc.). Signs from each of the three parties are shown here:

To limit the potential for electoral violence or misunderstandings, Somaliland traditionally designates specific days for each party to campaign. To limit the number of mass rallies during a time of COVID-19, this campaign limited each party to just two official campaign days. Due to my travel schedule, I was personally unable to witness any UCID Party rallies. The two photos below show a Kulmiye Party rally in a small village outside Sheikh and a Waddani Party rally in Burao.

The election was an enormous financial and logistical burden for a small, unrecognized country like Somaliland to pull off. By some accounts, Somaliland financed approximately 70% of the total electoral costs from its own resources with some international assistance from Taiwan and several European countries contributing the remaining funds. To minimize the potential for interference by local clan elders, Somaliland continued its past practice of largely employing university students as poll workers and sending them to different regions of the country. In Burao, for example, many poll workers we met were students from the University of Hargeisa. This would be the equivalent of sending IU Indianapolis students east to Ohio or west to Missouri to work elections there while sending students from the University of Kentucky or Michigan State University to work elections in Indiana. Simply moving chairs, tables, ballot papers, ballot boxes, etc. around a country with very minimal road infrastructure was an enormous challenge as the photo below gives one small indication of.

To facilitate the movement of election supplies and materials as well as poll workers and international and domestic observers, Somaliland prohibited vehicles from moving from Sunday at 6:00 PM before the election through to Tuesday evening after the election was concluded. The only vehicles allowed to move were ones that displayed special license plates issued by the NEC. The NEC plate for the vehicle I used is shown here.

To ensure the safety of its international observers, Somaliland requires that we travel with protection from Special Police Unit (SPU) officers anywhere outside the country’s capital city of Hargeisa. The photo below shows me with one of the funniest and most colorful SPU officers assigned to protect us. Like many Somali people, I have no idea what his real name is because everyone calls him by his nickname of “Kormeer” which translates as inspection or inspector. We appreciate him and his colleagues not just keeping us safe but doing so with style, humor and positive attitudes.

On election day, polls opened at 7:00 AM but our day as international election observers started at 6:00 AM. As was the case in 2017, the first thing you notice when approaching your opening polling station is hundreds of people lined up outside long before the polls open. In Somaliland, a traditional Islamic country, male and female voters typically line up in separate lines. The photos here show men and women lined up before the polls opened at Koosaar, a camp outside Burao for internally displaced persons (IDPs) who were displaced by a severe drought from Somaliland’s far eastern regions.

Before the polls open, international observers are supposed to verify whether all necessary materials are in place at the polling station and verify that the ballot boxes are empty and are sealed properly. It was also our first chance to see the actual ballot papers used. The first photo shows the parliamentary ballot paper used in Burao while the second one shows the local council ballot paper used in Burao.

At most polling stations, voters cast ballots from 7:00 AM – 6:00 PM. A few polling stations closed for lunch and the one I observed at closing time paused voting for evening prayer time. Such breaks were not supposed to happen. At first, I thought they were closing the station and denying the 20 or so people in line the chance to cast their ballots. I soon figured out, however, that it was a brief hiatus for prayer time followed by a reopening of the station about 20 minutes later. To accommodate all the voters in line before 6:00 PM, this polling station ended up staying open until about 7:40 PM.

In the 15 polling stations I personally visited, a few minor problems were apparent but nothing that indicated fraud or malfeasance. Perhaps the most serious issue I witnessed was one unsealed voting box at one of the stations I observed. All ballot boxes are supposed to be sealed like the one shown in this photo.

In one station, we witnessed an unsealed local council ballot box.

The election officials at this station were aware that this was a serious problem and had called the NEC regional headquarters to request that seals be brought out for this box. The box was also publicly displayed in the middle of the polling station in full view of domestic, international and political party observers. We did not see any attempts to stuff or tamper with the unsealed box.

We saw a few polling stations that had two or three small steps which might have been a problem for disabled voters. There also appeared to be several cases of underage voting. Somaliland’s IRIS-based voter registration system has been highly effective at stopping double or multiple voting but it cannot verify a voter’s age in the absence of a national birth registry. Finally, Somaliland’s electoral process consistently breeches international norms on ballot secrecy, but this does not appear to be a problem or issue for Somali culture. Many voters would walk into a polling station and loudly proclaim they wanted to vote for X or Y candidate. The NEC staff would then either show them how to do this or, in some cases, do this for them. They would then show the ballots to any domestic, international and/or political party observers present to demonstrate that the voter’s intent had been followed. In other cases, voters would mark their ballot papers secretly but then bring them to the political party observers (who worked together amicably at ever polling station I visited) and ask them to verify that they had marked their ballots correctly. The secrecy of the ballot was violated repeatedly but it was done so by the voters themselves and not against their wishes in any way.

Another minor logistical problem was that the ballot boxes used for the presidential election which were sufficient given its much smaller ballot papers with only three candidates on them struggled to accommodate the much larger ballot papers used in this election. By mid-day or late afternoon, many ballot boxes were basically full, and voters were forced to cram ballot papers into them, with increasing difficulty as voting progressed. Many elderly voters required assistance in getting their ballots successfully into the box. The photo below shows how full the ballot boxes were at the Saylada Xoolaha polling station we observed at closing time.

After the polls closed, NEC staff opened the ballot boxes in front of all election observers and then read the votes on the ballot out publicly while showing them to other staff and observers so everyone could see that the results being read out were accurate.

Another logistical problem given the large size of the ballots and the large number of candidates on each one was physically sorting the ballots by each candidate. In the Saylada Xoolaha polling station, this resulted in dozens of different ballot paper stacks being piled across the floor.

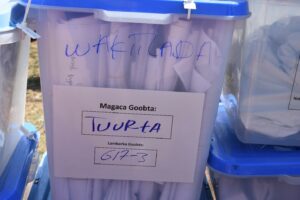

The final stage of the process we got to observe was seeing the resealed ballot boxes with recorded results from each polling station being delivered to the regional NEC headquarters for tabulation.

While observing the ballot boxes lined up and waiting to be processed, we came across several from polling stations we had observed on election day including this box from the Tuurta polling station.

In the wake of the elections, the Waddani and UCID parties announced that they would form a coalition to secure the majority of seats in Somaliland’s parliament. Waddani won 31 parliamentary seats, Kulmiye won 30 and UCID won 21 seats, thus giving the Waddani-UCID coalition a combined 52-seat majority in Somaliland’s 82-seat parliament. This returns Somaliland to the situation it found itself in after the 2005 parliamentary elections when a president from one party (then UDUB) found himself confronting an opposition-controlled lower house of parliament (then a Kulmiye-UCID coalition). Today, Somaliland’s President Musa Bihi Abdi from the Kulmiye Party also finds himself facing a lower house of parliament controlled by two rival parties. Although this situation with the executive branch controlled by one party and the legislative branch controlled by other parties happens with some frequency in the United States and Western Europe, it is extremely rare in sub-Saharan Africa. Kulmiye did somewhat better in the local council elections, securing the largest number of seats (93) but still falling short of the Waddani (79) – UCID (48) coalition which controls a combined 127 seats.

It is truly an honor and privilege to be invited by another country to observe their electoral process. Hopefully, this blog gives you some idea of what the process involves and how it is conducted, although it probably fails to convey the grueling nature of a 17-hour day that runs from 6:00 AM until 11:00 PM. The official report by the 2021 Limited International Election Observation Mission should be out in the next three-four months. If anyone wants to see what a full election observation mission report looks like, you can find our mission’s 2017 observation report on the presidential elections here.

Scott Pegg is a Professor in the Department of Political Science, IU School of Liberal Arts at IU Indianapolis