A former British colony, Somaliland proclaimed its independence from Somalia in 1991. Although it has been largely peaceful since 1997, Somaliland’s sovereignty remains entirely unrecognized. It is a paradigmatic example of what IUPUI Political Science Professor Scott Pegg terms “de facto states” – political entities that control territory, provide governance, secure popular legitimacy and yet remain largely or entirely unrecognized by the international community.

Somaliland’s lack of sovereign recognition has not prevented it from making significant progress toward consolidating a viable electoral democracy. It has now held six direct elections including local council elections in 2002 and 2012, parliamentary elections in 2005, and presidential elections in 2003, 2010 and 2017. Somaliland’s democracy has also survived several shocks or crises including the unexpected death of President Egal in 2002; his replacement by a vice-president from a minority clan in accordance with Somaliland’s constitution; an incredibly close 2003 presidential election with an initial margin of victory of 80 votes whose result the loser accepted; two opposition parties winning control of Somaliland’s parliament in 2005; repeated delays to a presidential election originally scheduled for 2008 but not held until 2010; and the implosion of the country’s previous ruling party, the United Peoples’ Democratic Party (UDUB), after its defeat in those elections.

With the incumbent President Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud ‘Silanyo’ not seeking re-election, the 2017 presidential election was widely seen as a watershed event in Somaliland’s history. Professor Pegg and Dr. Michael Walls’ pre-election assessment was published in The Washington Post one week before the election.

International election observers have monitored Somaliland’s elections since 2005. Although their reports have generally been positive, the International Election Observer Report on the 2012 local elections in Somaliland highlighted several problems with multiple voting which ultimately led to Somaliland adopting sub-Saharan Africa’s first biometric voter registration process for the 2017 presidential elections. In November 2017, Professor Scott Pegg was one of 60 international election observers deployed to monitor Somaliland’s presidential election campaign.

To serve as an international election observer, Pegg had to complete a six-part training module on election observation designed by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). International observers also underwent three days of intensive training in Hargeisa, Somaliland before being deployed to the field.

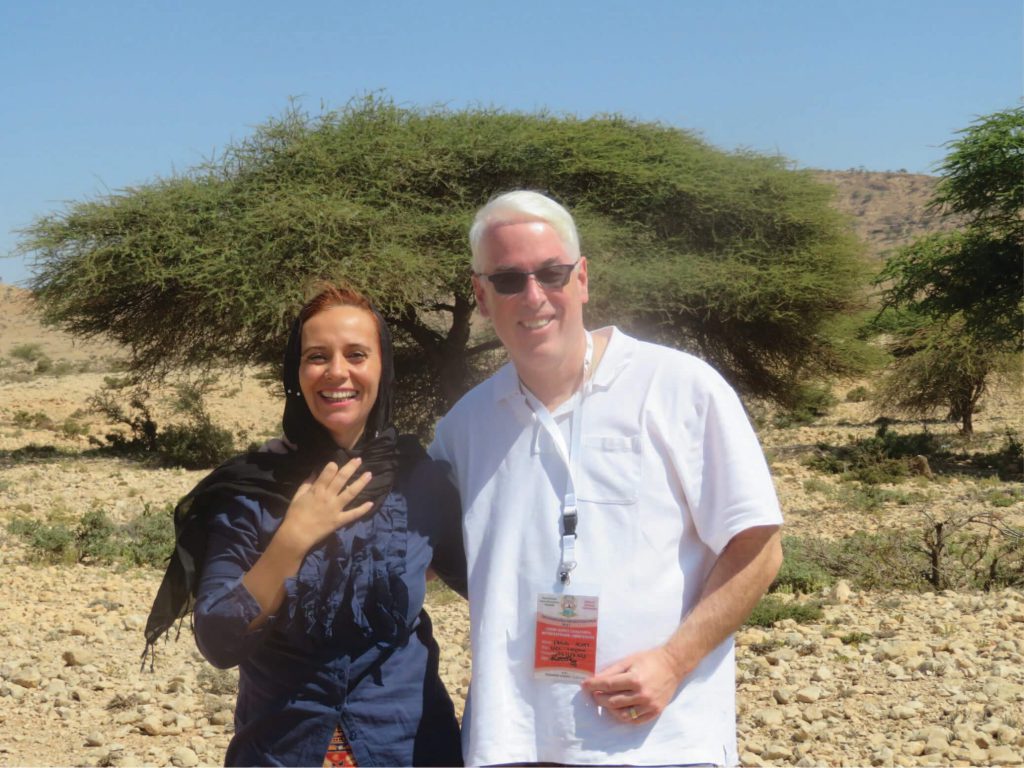

The 60 international observers were divided in 30 teams of two persons each. The teams were balanced to ensure gender diversity and home country diversity. Professor Pegg’s team partner was a Portuguese professor named Alexandra Dias.

Pegg and Dias were one of five teams deployed to the Burao region. Burao is Somaliland’s second largest city and was widely perceived to be one of its equivalents to what we call “swing states” in the US – places like Florida or Ohio where the vote could go either way. Four of the five teams deployed to Burao were charged with observing the vote at various polling stations throughout the city. Pegg and Dias were assigned to the rural areas south of Burao. They ultimately ended up observing nine polling stations – two in Burao and seven in rural villages south of it.

On election day, November 13, 2017, their day started at 6:00 AM by arriving at a polling station in Burao before it opened. Voting started at 7:00 AM local time but hundreds of voters were lined up to vote hours before the polls opened. In Somaliland, men and women line up in separate lines and this photo shows women waiting in line shortly after the polls had opened.

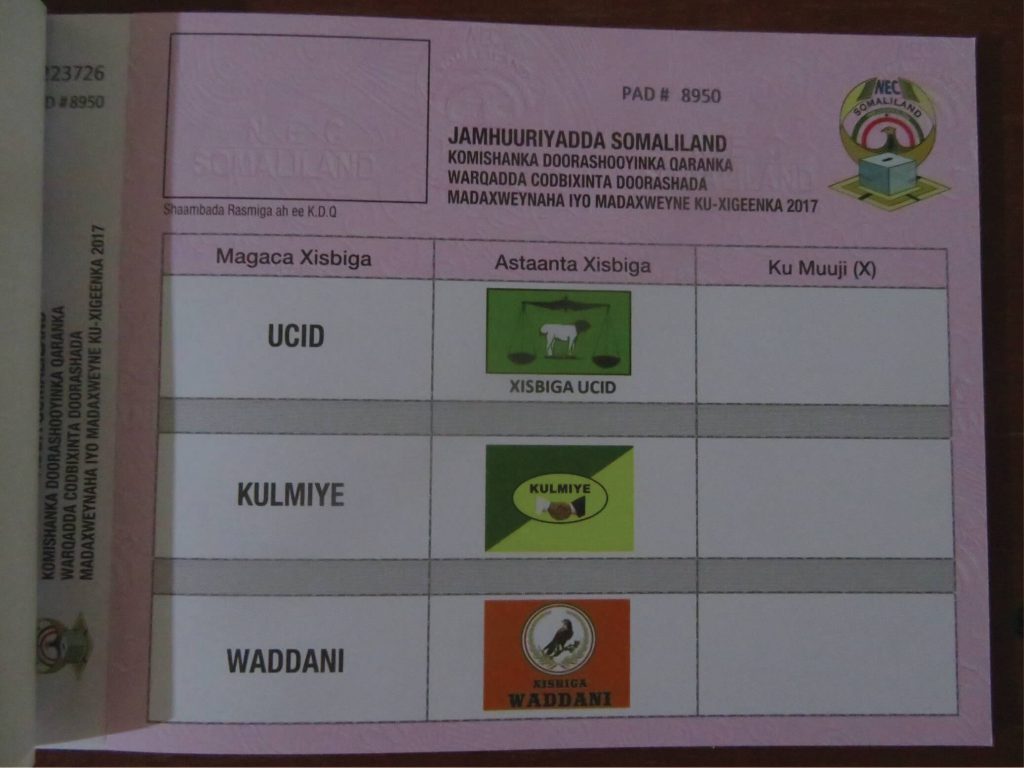

Under Somaliland’s Constitution, presidential elections are contested by three national parties. This election was perceived to be a close contest between two of the parties, Kulmiye and Waddani, with the third party, UCID, not seriously in the running. Voters had to mark one paper ballot with their choice.

After observing one polling station opening in Burao, Pegg and Dias headed out on a single lane dirt road to travel into the rural areas. For long parts of their trip, they typically saw more livestock than people.

Polling stations were typically housed in schools. Typically, they had four polling station officials working at each location plus domestic observers, political party observers and international observers.

The highlight of the day for Pegg and Dias was being treated to a lunch of rice, spaghetti and camel meat in the village of Sanyare. In contrast to the bad publicity they often receive, Somali people are incredibly warm, generous and welcoming and they appreciated international election observers trying to ensure the integrity of their polls.

After a long return trip, Pegg and Dias watched another polling station close and count the vote in Burao. The chairwoman of the polling station opened the ballot boxes and read out each vote. Other polling station workers then showed the ballots to the domestic, political party and international observers present. The entire process was transparent and straightforward.

Ultimately, Musa Bihi Abdi, the Kulmiye party candidate secured an outright majority with 55.1 percent (305,909 votes) to 40.7 percent (226,902 votes) for Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi ‘Irro’ and the Waddani party and 4.2 percent (23,141 votes) for Faisal Ali ‘Warabe’ and the UCID party. In securing more votes than the other two parties combined, Kulmiye’s margin of victory of 79,817 votes exceeded most expectations. Domestic and international observers found minor problems with the election but generally hailed its peaceful and orderly nature. If you are interested in learning more about this election, the International Election Observation Mission report and Professor Pegg and observation mission head Dr. Michael Walls’ academic journal article in African Affairs are excellent places to start.