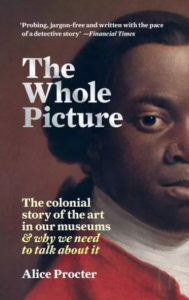

The Whole Picture: The Colonial Story of the Art in Our Museums & Why We Need to Talk About It, by Alice Procter. London: Cassell, 2020.

REVIEWED BY MORGAN COFFMAN

How many times have we wandered through the halls of museums, marveling at the art hanging upon the walls and squinting to read the labels of title, author, materials? At times, I’m sure we have all wondered about what was going unsaid in these short, official descriptions. It was art historian Alice Procter’s intention to bring these lost and hidden stories to light in the hopes that they might illuminate the many ways that museums and the public have created, collected, and displayed art throughout the years.

Procter’s book, The Whole Picture, goes into great detail to recount the lesser-known histories behind the famous works of art displayed in public institutions across the globe. By sharing this knowledge, she hopes to create discussion around whether museums have the right to display these objects, or if it is even possible to show them without furthering the harm and conflict they have originated from and contribute to. She invites us to come to our own conclusions about the places for these types of artifacts after being provided the whole picture.

A great deal of the pieces displayed in museums today can be traced back to colonialism, in which colonizers extracted wealth and valuables from their territories to further their image and establish their power and authority over the native populations. It is this legacy that haunts the halls of museums today, despite the many changes that have been made in an effort to separate the past from the present. It is here in the early days of museums that Procter begins her analysis.

Over the course of four sections, Procter describes the evolution of these institutions from their earliest exhibitions to the future of museums that have been envisioned by creators and curators. Each section contains a series of examples in which she tells the arduous history of prominent pieces, occasionally containing images to further illustrate her point. The first of these sections, titled The Palace, starts with the cabinets of curiosities that were owned by the rich and powerful to show off treasures from their conquests, detailing the dark histories behind Egyptian sarcophaguses, Indian diamonds, and British colonial paintings. Following this is The Classroom, in which the museum became a true public institution dedicated to cataloging national treasures and educating the audience through a narrative of propaganda and indoctrination. This can be seen through paintings like those done of Mai, the first Pacific Islander to visit Europe, in which he was depicted as a representation of the ‘noble-savage’ and a living specimen to educate the British public. The Memorial goes on to show a more modern interpretation of museums as places for emotion and reflection on the past, often done through the display of human remains. The final section, The Playground, explores the potential future of museums by examining the work of various museum professionals and artists that have reframed and recontextualized their spaces and exhibits through interactive art pieces and tours featuring critical commentary. Works such as Crowd Control are included here for their ability to challenge visitor’s perceptions of the museum and question what is found within. In the conclusion, Procter analyzes the struggles of museums as they move from passive collections that perpetuate the harmful heritage of their artifacts to active spaces highlighting forgotten histories and drawing attention to the atrocities of the past without bringing them into the present.

The Whole Picture was intended as instructions from an art historian to help a broad audience reflect on and reconsider the types of objects that are venerated in museums, although museum professionals may also find the work enlightening in regards to its advice for creating a more respectful, comprehensive, and political institution. It provides many detailed examples of how the crimes of history can be recreated through the displays in museum galleries, even though the book at times contains an overabundance of information that is not entirely relevant to the purpose and interpretation of the pieces. This can be seen in the very first section, where Procter spends a great deal of time examining the specifics of transactions behind the Pitt’s Diamond, details that are not necessary to understand their story and end up diluting the purpose of the artifact’s inclusion in the book. Despite these concerns, The Whole Picture presents an interesting perspective on a current and controversial debate among museum professionals about whether or not, and how, a museum can accurately and wholly be decolonized.

While it often meanders around the point and rarely speaks directly on the field of museums, the book is overall a worthwhile read. It can be very informative for those looking for more background on the dark histories of art currently on display in museums, and the ways that these pieces could be recontextualized and reframed to better serve the needs of a modern audience in ways that are more ethical and equitable for all.

Morgan Coffman is a first year MA student in the Museum Studies Program at IUPUI.