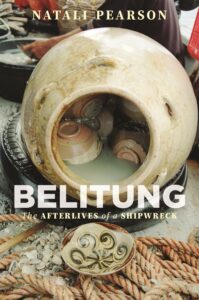

Belitung: The Afterlives of a Shipwreck, by Natali Pearson. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2022.

REVIEWED BY THOMAS CRAIN

In Belitung: The Afterlives of a Shipwreck, Natali Pearson, an underwater cultural heritage researcher, attempts to untangle the many lives, contexts, and controversies of the Belitung shipwreck by exploring it through a unique contextual framework. The Belitung was a 9th-century ship of Middle Eastern origin carrying tens of thousands of Tang Dynasty ceramics and metals. The ship was sailing the Maritime Silk Road following the path of the monsoon winds, bringing the mass-produced goods to Southeast Asian and Middle Eastern markets, when it sank near the coast of present-day Indonesia’s Belitung Island.

In Belitung: The Afterlives of a Shipwreck, Natali Pearson, an underwater cultural heritage researcher, attempts to untangle the many lives, contexts, and controversies of the Belitung shipwreck by exploring it through a unique contextual framework. The Belitung was a 9th-century ship of Middle Eastern origin carrying tens of thousands of Tang Dynasty ceramics and metals. The ship was sailing the Maritime Silk Road following the path of the monsoon winds, bringing the mass-produced goods to Southeast Asian and Middle Eastern markets, when it sank near the coast of present-day Indonesia’s Belitung Island.

The first chapter analyzes the ship and its cargo in their first life, highlighting their importance in a vast and commercially connected network. In the second chapter, Pearson describes the Belitung’s first afterlife as sunken, lost objects and explores the political environments in Indonesia and the international underwater heritage sector in the 1990s that influenced how the shipwreck was salvaged. Using this context, Pearson investigates and scrutinizes the commercial salvaging of the Belitung’s cargo in the third chapter and details the marketing and sale of the artifacts. The fourth chapter examines the attempts of different countries, including Singapore, the purchaser of the main collection of recovered artifacts, to claim the Belitung as part of its cultural heritage, notably through the controversial Shipwrecked traveling exhibit. Lastly, in chapter five, Pearson delves into the eventual musealization of the recovered artifacts before concluding with a discussion about how underwater cultural heritage often lends itself to situations of contested heritage and questioning the effectiveness of strict international regulations on underwater cultural artifacts.

Throughout the book, Pearson offers a nuanced viewpoint on the controversy surrounding the artifacts salvaged from the Belitung wreck based on a comprehensive contextual framework of local regulations, regional attitudes, and international conventions. The private, commercial salvage of the Belitung was not conducted up to the ethical standards of underwater anthropology, as it was carried out quickly with little anthropological research because the main goal was to recover as many artifacts to sell in the art market. Pearson does not condone the unethical practices of the salvage company, arguing that “commercial salvage was the least destructive option available at the time, and the only way in which this specific shipwreck could be secured from the immediate and devastating threat of looting” (64). This view, with consideration of the salvage method as a product of Indonesia’s political status at the time, was not held by researchers in the international underwater heritage community.

In response to the impending first run of Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds at the Smithsonian in 2011, the institution, which helped create the exhibit in partnership with Singapore, canceled the exhibit over ethical concerns about the salvage operation in response to outcry from the anthropology community. This prompted the Smithsonian to establish a “Shipwreck Advisory Committee” to discuss the merits of a revamped Shipwrecked exhibit and its ethical standing. The Western anthropologists on the committee feared the Smithsonian exhibit would condone the unethical salvage of the Belitung and the subsequent sale of the artifacts for profit. Thus, the committee decided to cancel the exhibit entirely and re-excavate the wreck site. Pearson criticizes the committee’s decisions, declaring that “the decision to re-excavate betrayed a fundamental lack of understanding about the Indonesian context . . . [because] apparently unbeknownst to the Shipwreck Advisory Committee, the site had already been surveyed by Indonesian archaeologists . . . in 2010” (103). The ill-informed recommendations from the researchers on the Shipwreck Advisory Committee further validate Pearson’s argument that commercial salvage was the best solution based on the contextual framework of the time.

As the controversy of Shipwrecked faded, artifacts salvaged from the Belitung have been displayed internationally, including in the United States. The first exhibit of Belitung artifacts outside of Singapore opened in late 2014 at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto. In anticipation of a backlash similar to what the Smithsonian faced, the exhibiting museum wrote a “position paper” discussing the legal and ethical dilemmas of the collection to spark “discussion about the protection and preservation of underwater cultural heritage and encourage reflection on the responsibilities of managing this and other shared heritage” (111). The ideas espoused in the position paper set a standard for similar discussions of the ethics of displaying artifacts from the collection in subsequent exhibitions throughout the world.

Natali Pearson’s nuanced analysis of the many lives and contexts of the Belitung shipwreck offers a grounded perspective on the salvage and display of the ill-fated vessel’s cargo. By giving equal acknowledgment to the political context in Indonesia where the wreck was found, the decisions taken by the commercial salvagers and the government become clear and justifiable, as opposed to looking at the situation solely through the idyllic lens of international ethics codes on underwater cultural heritage. This holistic approach is vital for museum professionals because “while notions of shared heritage can be inclusive,” Pearson contends, “they can also be deployed to exclude local stakeholders from decision- making processes” (138).

Thomas Crain is a first-year MA student in the IU Indianapolis Museum Studies Program.