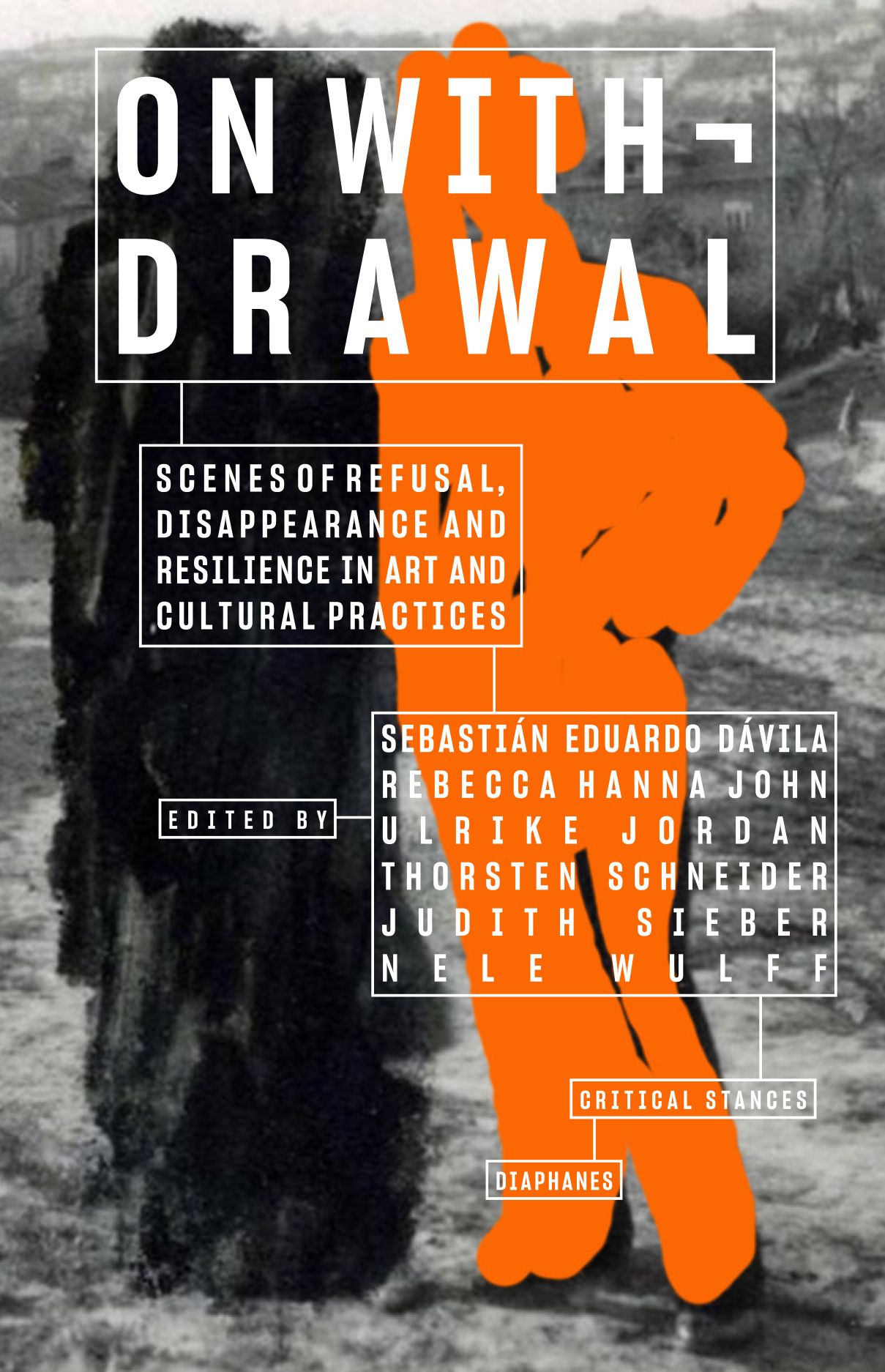

On Withdrawal—Scenes of Refusal, Disappearance, and Resilience in Art and Cultural Practices edited by Sebastian Eduardo Dávila, Rebecca Hanna John, Ulrike Jordan, Thorsten Schneider, Judith Sieber, and Nele Wulff. Diaphanes & University of Chicago Press, 2023.

REVIEWED BY GRACIE COLLIER

Museums foremost serve the public, and all too often the public is considered only in terms of the majority or those in power. How can any field address the unaddressed, especially when society only reflects the addressed? In the book On Withdrawal: Scenes of Refusal, Disappearance, and Resilience in Art and Cultural Practices this rarely covered area is explored in a series of discussion and think pieces from a multitude of authors and editors. That which is rarely covered the book calls “withdrawal,” “that which withdraws itself or [that] which is being withdrawn” (p. back cover). Withdrawal can be action or non-action; an intentional decision by a group or a state forced upon people by those in power. Withdrawal is a concept often expressed in marginalized groups, or those in opposition to the society of the day. The study and discussion around how to choose non-action, from refusal to resilience, provides a radical means for museums to best serve the public trust.

The text is split into four overarching sections, an Introduction and Summary, a section called Passivity, Failure, and Refusal, a section on Disappearance and Remembrance, and finally a section on Resilience and Resistance. The first part, “… explores the potentiality in non-heroic acts of not-doing” (p.10). Often institutions are expected to answer calls to action and deemed complicit in any lack of action in response to the call. However, in the essay by Kathrin Busch what she names the “aesthetics of inability” (p.36), the shamefulness and grotesque appearance reveal a fundamental truth to life and an otherwise inaccessible form of knowledge. When offering any kind of education or description, awareness of pervasive biases and societal expectations that might hinder a valid and genuine experience of the world should be recognized. Both the single, invariable truths of life and the kaleidoscope of truths based on perspectives become threatened in the face of societal-defined pressures. Withdrawing from such pressures allows museums to go through what Mutlu Ergün-Hamaz refers to as a “detox from a racial drug” (p.71), that is “…similar to an addict who is in denial of their addiction, being in denial of White supremacy, [the racial drug], means being in denial of something harmful to society as a whole” (p.73). While written about a specific cultural climate and incident, the “drug” in a broader sense can also be Abelism, Transphobia, and so on. Since museums provide education on topics like art and culture, the study and use of non-action allow for a literal revolution in the field. Instead of trying to tell stories of “others” in a tailored format, museums can allow the presented groups to tell their story.

The section on Disappearance and Remembrance considers how by exposing any field for discussion, institutions and those in positions of societal prestige can still enact violence and a forced withdrawal upon subject matter. Just in text alone a label for a museum piece can impose removal upon the subject matter, especially if said piece comprises the voices of the few. As Sebastian E. Dávila and Jordan Ulrike observed, “…to write means to make something visible, but it can also serve to hide that which is left unwritten” (p.165). “That which is left unwritten” can serve as a powerful tool for the exhibition subject as long as it’s handled in a manner in line with the desires and techniques of the subject. When written by the hand of the majority the unspoken instead becomes “…an instrument for violence” (p.165), a forced withdrawal of the group or topic being discussed. Often those marginalized are expected to speak for their group and to give exemplary testimony. However, what if instead museums allowed for the voices of the subject matter to dictate not just text but also a call to observe moments of intentional withdrawal; to explore a perspective radical from any standards by taking radical decisions in light of practiced actions. As beautifully put by S. E. Dávila and U. Jordan, “…maybe the emptiness itself is more powerful than any informational sign could be” (p.210).

The final section, Resilience and Resistance, challenges commonly practiced forms of withdrawal, how they might contribute to cultural stagnation and submission, and how to enact withdrawal to participate in cultural change. Resilience, or the choice to not fight back and simply withstand, today serves as a harmful method of withdrawal that ends up in involuntary acceptance of an unacceptable system. A great example of such can be found in the pandemic, where the populace often just grit their teeth and bore the struggle while trying to keep up as much normalcy as possible. Instead, the authors call for refusal, the outright show of not accepting something, to replace resilience. One method suggested, here by Sofia Bempeza, is to “…reclaim adraneia (inactivity)…[as] a way of reprogramming our mindsets. Instead of adapting our activities to the newest institutional standards…[she] propose[s] to insist on the temporary time of adraneia…” (p.313). As stated earlier, often institutions can feel an expectation to answer a call to action and feel shame for failing to answer promptly. Perhaps, the powerful approach is to allow for a time of adraneia to formulate a thoughtful and more long-lasting substantial action in response. Museums, as institutions dedicated to the preservation of the past and present, should allow their naturally slower pace to serve as a means to better choices. In turn, such thoughtful and time-consuming approaches will conversely serve the public by granting a more thoughtful environment to engage in.

While never addressing museums, the book On Withdrawal: Scenes of Refusal, Disappearance, and Resilience in Art and Cultural Practices presents an open-ended discussion on the concept of withdrawal, of in-action, that carries long-reaching implications and considerations for many fields. Being a field that deals in the cultures of communities, museums have a particular imperative to consider mindsets contrary to the expectations of the day, especially the expectations of the larger whole. Any museum professional who reads this book will certainly have their world opened to a variety of perspectives and approaches to curation and education that can radically impact their audience for the better.

Gracie Collier is a first-year MA student in the IU Indianapolis Museum Studies Program.